Team Pattern #2: The Matrix Team

This is the third post in my blog series on team patterns, and this time we will look at the matrix team pattern.

A matrix team is a temporary product (or project) team, which is made up of specialists from different functional areas. The idea with the cross-functional nature of the team is to increase collaboration between different functions to create better products and faster releases.

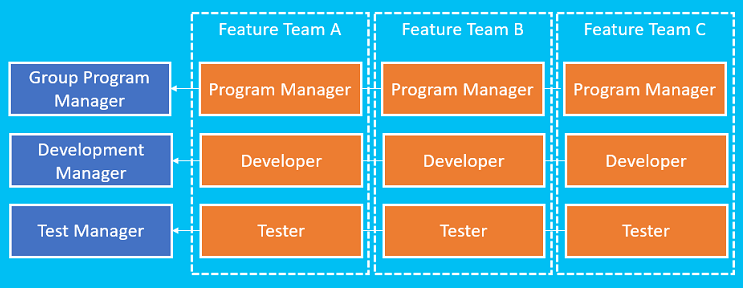

An old-school example of this team pattern is Microsoft Solutions Framework (MSF), which was hot back when Microsoft ruled the (software) world:

A feature team is usually focused on a product area and will typically last for the duration of a product release or longer. For example, in Microsoft you would have multiple feature teams working on Microsoft Excel, and one of them would focus on Excel Macros.

An example of the members of a feature team could a Program Manager (responsible for functional specifications and project management within the team), 4 developers, and 2 testers. The Program Manager will tell the developers and testers which is the most important feature to work on and handle the planning and coordination of the feature team’s work.

However, developers report to a development manager who provides guidelines on how they should do their job (e.g., job descriptions, development process, engineering practices, coding standards) and be responsible for people management (e.g., promotions, training, move to a new team, etc.) — and it is the same for the other roles, so program managers report to a group program manager, and testers report to a test manager.

The underlying idea is that it will encourage cross-functional collaboration when specialists are literally on the same team, but the specialists will continue to report to a functional manager who is an expert in their area of expertise.

Tuning the Matrix

The most common parameters to tune in this team pattern are the influence of the line manager on the team’s work (degree of team autonomy) and the duration of the matrix team (short-lived versus long-lived).

Yammer: Very short-lived matrix teams

A modern variation of this team pattern is used by Yammer, a social network for enterprises. A key difference between Yammer and Microsoft is that Yammer continually deploy new features to production and don’t have major product release like Microsoft used to have for their shrink-wrap products.

Yammer’s developers share the ownership of the entire codebase, so there is no thing such as “my code” or “my module”. Each time a task needs to be performed on the codebase, they establish a temporary team for this specific task. When the task is done the code is released to production and the task force is disbanded and developers are free again to join new ad-hoc team to address new tasks.

The thinking is that this is highly agile, and people will not be limited to work on a single product area but can quickly go wherever there is the biggest need for them.

The development manager is responsible for developers within his or her technical area, such as Ruby on Rails, Java, or React. But the development manager is no longer defining guidelines for how the developers should work, but instead a coach who is focus on turning his or her developers into top-notch experts in their given technology.

Spotify: Long-lived, autonomous matrix teams

At Spotify, an online music player, they take a different approach and encourage long-lived, stable matrix teams (which they call “squads”). Their reasoning is that it takes a long time to master a product area, such as Spotify Radio, and mastery is needed to build an awesome product for their users.

They also empower their matrix teams and give them greater autonomy than many more traditional matrix organizations.

However, Spotify still have line managers (which they call “chapter leads”), but with the important twist that the line manager is also an active member of a matrix team (for example, as a back-end developer) to make sure he or she stay in touch with reality.

Strengths

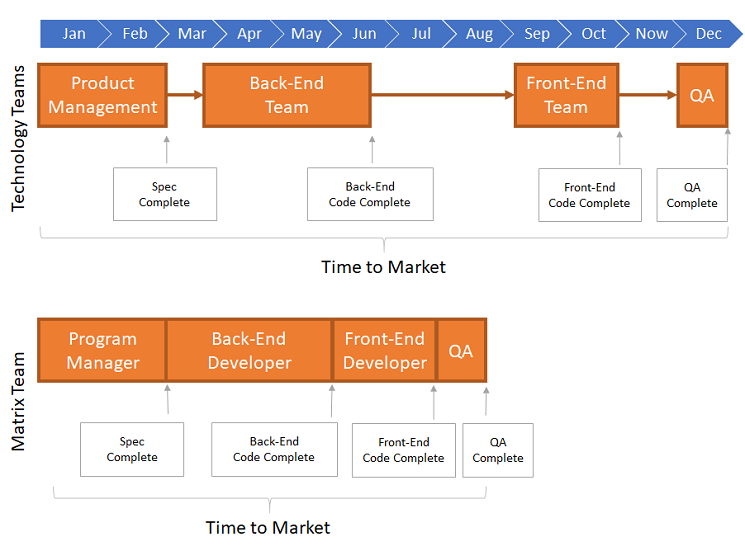

The primary strength of the matrix team (compared to the technology team pattern from the previous post) is that it fosters much closer collaboration across functional disciplines. Now the developers and testers are part of the same team; especially, if the program manager successfully makes a shared vision for the product area.

On top of that being a cross-functional team means that all the necessary skills will be immediately available within the team, so there won’t be these gaps between the teams which we saw in the technology team pattern. This improves time to market:

It also encourages developers and testers to learn more about the business domain, such as banking or medicine, that the matrix team is working in. This is really useful when it is a highly complex business domain with lots of counter-intuitive business rules. For simple domains, such as social networks or blogging, it may be less important.

It also brings engineers closer to the business and makes it easier to see how they contribute to the success of the company, while they can still continue to seek mastery within their chosen technology and continue to report to a line manager who appreciates and understands their technical work. The line manager also enforces alignment and quality across teams, and the engineers will have a second opinion (and supporter) in case of a powerful and persuasive program manager on the team or they feel uncomfortable with the decisions taken within the team.

The matrix organization also scales well and can be used for delivering very large products. Microsoft released many of their greatest hits, such as Windows and Microsoft Office, using this team pattern. They were even able to compete with young startups, such as Netscape, while using this model. Obviously, Microsoft used some dirty business tricks to win the browser war against Netscape, but they would not have been able to compete with Netscape if they had not been able to keep up with Netscape’s development speed.

Weaknesses

In theory, a matrix team has a high degree of autonomy, but in practice multiple line managers will often enforce controls that limit the team’s autonomy and the team will need to consult with the line managers before trying anything too radical.

There is also a risk that work process inside the team will turn into small waterfalls with extensive handovers between the disciplines inside the team. This can happen when the line manager is not actually part of the team but defines the process that his or her people must follow within the team.

There is also a risk that the line managers may not see the big picture and start to suboptimize for their functional area. For example, the test manager wants to introduce NASA-like quality controls, while the customers are actually happy with the current quality level and is much more interested in getting new features quicker (at the current quality level).

Many developers who worked in a matrix team feel like they have two managers (i.e., the development manager and the program manager) and they often receive conflicting signals about what is important. For example, the program manager says that the developer can skip the unit testing to meet the deadline, but the development manager says that unit tests must be written for all new code — and the developer is caught in the middle. Unclear or overlapping responsibilities are a frequent source of conflict and frustration in a matrix organization.

Decision making related to how the team works may even turn into a lengthy process as multiple line managers may need to be involved in a single decision. For example, the development manager wants to introduce static code analysis (and pay the technical debts it reveals), which should be a pure development activity. But the program manager feels that it will delay the development activities already on the team’s roadmap, so she wants to be involved. The test manager feels that it is an initiative related to quality, and hence, he should have a say in it, and incorporate it as part of an overall test strategy.

To address these weaknesses, some engineering organizations introduced product teams where they would continue to organize teams around product areas to harvest the benefits of cross-functional teams, but to boost the team’s autonomy and speed up decision making, they decided to drop the matrix organization (with multiple line managers) and instead have the all people on a product team — regardless of their specialties — report to the same line manager.

We will look at this pattern in the next post in this blog series on team patterns. Stay tuned!