Winston Churchill: A First-Class Writer

Bernard Shaw wrote that, “the reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” This statement is perhaps exemplified no place better than in the life of Winston Churchill, Shaw’s contemporary.

Churchill was born into an English aristocratic family with all the expensive habits of this class, but unfortunately his late father had failed to leave him a family fortune that is needed to sustain such a lifestyle. A reasonable man would have reduced his expenses to meet his actual income — but Churchill never thought small — so he decided to simply raise his income until it met his expenses and if his expenses outgrew his income again, he would simply grow his income even more.

Now the curious reader will probably agree with Churchill’s logic in theory, but may ask if an English aristocrat in the 20th century was educated with lots of market-relevant skills that could actually produce an income? And on top of that a substantial income that could support an extravagance lifestyle with French champagne, Cuban cigars, world travels, country house, servants and so forth?

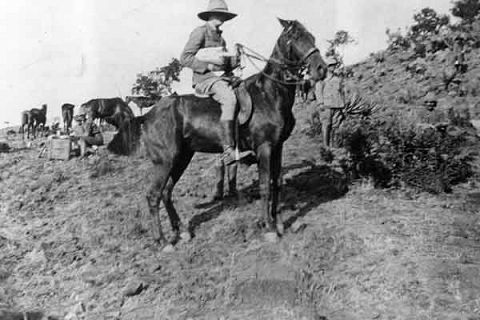

To start from the beginning, when Churchill was a young officer in the British Army, he was desperate to seek out action as courage in battle was essential for promotion. So when a military expedition started in Northwestern India (today, Pakistan) to punish the local tribes, he wanted to join despite the travel expenses were more than what his mother’s endowment could support. So he made an agreement with The Daily Telegraph, a newspaper, that he would write articles about the expedition to the newspaper in exchange for them paying his travel expenses.

The series of articles showed that he had a talent for words and after the expedition had ended, he turned the articles into his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, which is still a highly readable book about his baptism of fire, which he describes as a delightful experience: “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.”

Churchill quickly realized that his talent for words could be his road to financial freedom, so he continued to hone his writing skills and moved from journalism to more substantial literary works. He was never afraid of demanding a high fee for his writings and he refused to give in to anyone who wanted a low price. At some point the frugal Rockefeller family approached him to write the biography about the late John D. Rockefeller, supposedly the richest man in history, but the Rockefellers withdrew their offer in horror once they saw the fee that Churchill demanded for writing the biography. So Churchill never wrote the Rockefeller biography, but instead continued with other works supported by more generous sponsors.

His Writing Habits

Obviously you can only demand unreasonable high fees, if your writings are of such an outstanding quality that people still think they get value for their money. And at the same time you need to produce them at a rapid pace, so your income stream doesn’t run dry. So how did Churchill manage to produce great works at a high speed while still having time for a political career?

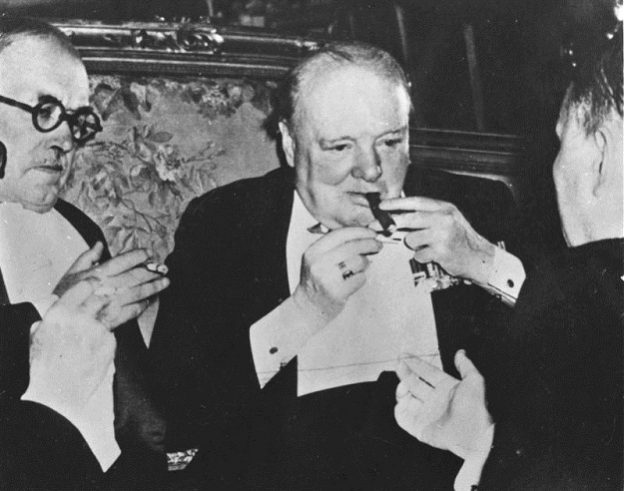

Churchill preferred writing late in the evening and usually started around 10 PM when dinner ended and continued writing until 2 AM. In these late-night writing sessions Churchill would be standing by his upright desk with a whisky soda in one hand and a cigar in the other while using his formidable oratory skills to turn historical events — for he wrote mostly about history and politics — into a captivating narrative that his sectary would dutifully write down. His research assistant would also be there ready to supply facts as needed and spot inaccuracies in the narrative.

As Churchill sharpened his writing skills over the years, he also developed a set of habits that he followed to produce his successful works:

- Give the reader a good ride: When Churchill wrote Marlborough: His Life and Times he said to his research assistance, “I aim to give the reader a good ride”. This focus on telling a great story, rather than being overly analytical, is probably why his books are still a good read for the casual reader.

- Dictate, rather than write: Churchill dictated his words to his sectary, rather than writing them himself. The reason for this might be that speaking is the natural medium for a great orator, such a Churchill, so it gives the narrative a more natural flow. Another reason is that it’s faster to speak than to write, so he could simply get more done in less time by dictating.

- Use short words: Churchill said, “Short words are best and the old words when short are best of all.” Churchill knew that short English words (which are often derived from Anglo-Saxon, rather than Latin) have a more powerful effect on the reader. As noted in this style guide, when Churchill asked for material help from America in the fight against Hitler, he didn’t say “Deliver to us the implements, and we will complete the assignment”, instead he simply said, “Give us the tools, and we will finish the job.“

- Seek feedback: When working on a manuscript Churchill was relentless in seeking feedback from others. For instance, when writing the Marlborough book he sent 308 letters asking for answers to specific questions, or for the recipient to review his manuscript.

- See it in print before it’s final: Churchill would always get his draft manuscript set up by a typographer and printed, so he could see what the final product might look like while he still had a chance to edit it — and this was before the computer, so it was a cumbersome process. Even if his publisher insisted that this was an unnecessary step in the creative process, Churchill would offer to pay for this out of his own pocket.

- Take a siesta: When Churchill was a young war correspondence in Cuba, he picked up two lifetime habits — the first being smoking Cuban cigars and the second being taking a siesta. At around 5 PM each day, he would sleep for 1½ hour and this was no power nap where he just sat in a chair. No, he would get his clothes off and go to a proper bed and sleep. Afterwards, he would take a bath and get dressed for dinner. Churchill said that taking a nap allowed him to work 1½ day in a single day and the nap was probably also needed to have the energy for his late-night writing sessions.

- Set a daily aim: While writing his biography on Marlborough and building a cottage, at the same time, Churchill had the aim of laying 200 bricks and writing 2,000 words per day. He knew if he managed to do both then it had been a good day.

Churchill followed these writing habits throughout most of his career and was a highly productive author who wrote 15 books — some of which were multi-volume works consisting of more than 4,000 pages — together with a vast amount of articles, speeches and letters. You can almost be surprised that he also had time for a political career…

His Finest Hour

When Churchill was chosen as Prime Minister in 1940 to lead England in the war against Hitler, he wrote in his diary, “I felt as I was walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

While his military and political careers had undoubtedly prepared him for this grand challenge, his mastery of words was an equally indispensible tool when he needed to strengthen the moral of the British people, which was seriously needed as Hitler continued to move from one aggressive triumph to another.

And Churchill did indeed mobilize his formidable writing skills in the defense of England. In less than two weeks, he wrote three speeches Blood, toil, tears and sweat, We shall fight on the beaches and This was their finest hour which are all are among the greatest speeches delivered in the history of mankind.

And England did not back down, but stayed in the fight until Russia and America also joined the war effort and together they defeated Hitler and won the war.

In 1953, his literary career was crowned with a Nobel Prize in Literature. When reading his books, or listening to his speeches during the war, you tend to agree with the Nobel committee that awarded him the prize for “his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.“